Salem Civic Center Historic District Salem, Oregon

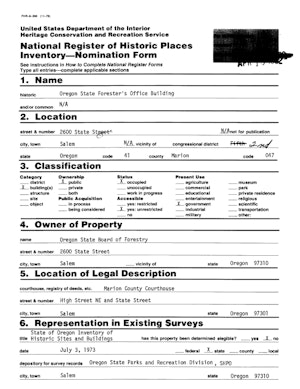

National Register of Historic Places Data

The Salem Civic Center Historic District has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places with the following information, which has been imported from the National Register database and/or the Nomination Form . Please note that not all available data may be shown here, minor errors and/or formatting may have occurred during transcription, and some information may have become outdated since listing.

- National Register ID

- 100008330

- Date Listed

- November 2, 2022

- Name

- Salem Civic Center Historic District

- Other Names

- Vern W. Miller Civic Center

- Address

- 555 Liberty St. SE

- City/Town

- Salem

- County

- Marion

- State

- Oregon

- Category

- district

- Level of Sig.

- local

- Areas of Sig.

- COMMUNITY PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT; ARCHITECTURE

Description

Text courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, a program of the National Parks Service. Minor transcription errors or changes in formatting may have occurred; please see the Nomination Form PDF for official text. Some information may have become outdated since the property was nominated for the Register.

Summary Paragraph

The Salem Civic Center Historic District – bound by Trade Street on the north, Commercial Street on the west, Leslie Street on the south, and Liberty Street on the east – sits on four-city blocks just south of the commercial downtown in Salem, Marion County. Constructed between 1970 and 1972, the property has five contributing resources – the Central Fire Station #1, Mirror Pond and Pringle Creek, City Hall Parking Garage, City Hall (including City Council Chambers), and Plaza Fountain – and two non-contributing resources – the Public Library and Library Parking Garage – within the nominated property boundary of 12.85 acres.1

The historic district is a Brutalist complex, comprised primarily of concrete and relies heavily on open space and connection between the resources not only to create an inviting space for the public but to soften the Brutalist style and materials. The Central Fire Station #1 is located on the northeast corner of the property and can be accessed from both Trade and Liberty Streets. Between the Central Fire Station #1 and City Hall Parking Garage is open park space including Mirror Pond, Pringle Creek, and sidewalks that connect the complex. The City Hall Parking Garage roof also features open space with concrete planter boxes. City Hall – which includes City Council Chambers – is located in the center of the property with access to the interior courtyard and city services from both the north and south elevations. Between the City Hall and Public Library buildings is the Plaza Fountain, an open space with decorative concrete elements surrounding a decommissioned water feature and statue.

The Public Library and Library Parking Garage are located furthest south on the site. The Public Library building – completed in 1972 – has been substantially remodeled, receiving additions to the south elevation in 1991 and seismic upgrades in 2020-21 that have greatly diminished integrity. The Library Parking Garage was constructed in 1991 – outside the period of significance – on top of a planned children's park and surface parking.

While these two individual buildings are no longer contributing, overall the Salem Civic Center Historic District retains a high level of historic integrity. It is in the original location, the setting has not been altered, and the design of the district – including the physical connections between the buildings and the common, unifying architectural details and materials – are highly intact. With the exception of the southern portion of the property, there have been relatively few material modifications and the workmanship of an early 1970s Brutalist complex is strongly represented. The Salem Civic Center retains high integrity of feeling and association.

Character-defining features that unify the district include the layout of buildings on the site to take advantage of the natural, terraced topography and existing water features, the square and rectangular shape of the buildings, the common concrete material, and similar design features on the buildings (horizontal lines, concrete columns, concrete parapets, etc.).

Narrative Description

Note: The following descriptions only includes a discussion of interior spaces if they are character defining (e.g., City Council Chambers). Given the nature of the buildings and changes in technologies and processes since 1972, the interiors have been continuously updated to accommodate evolving employee needs, though none of these modifications have diminished the integrity of the Salem Civic Center or the individual contributing resources. Further, the significance of the Salem Civic Center is grounded in the arrangement of the buildings and landscaping to each other and how together the complex encourages public participation in local government.

Setting and the Overall Site

The four-block Salem Civic Center is located on a hillside south of Salem's commercial downtown. It is bound by Trade Street on the north, Commercial Street on the west, Leslie Street on the south, and Liberty Street on the east. From north to south the Salem Civic Center includes the following: Central Fire Station #1, Pringle Creek and Mirror Pond, City Hall Parking Garage, City Hall (including the City Council Chambers), Plaza Fountain, Public Library, and Library Parking Garage.

Dispersed throughout the site are sidewalks, staircases, and ramps that connect the resources to each other and landscaping features like poured in place, concrete planter boxes, benches, and lighting. The landscaping softens the Brutalist elements of the campus, creating a more welcoming and balanced public space.

The Central Fire Station #1 is the northern most building and sits at the corner of Trade and Liberty Streets. It is lowest in elevation and the site increases in elevation heading south. The City Hall and Public Library buildings have the most commanding views and prominence, both looking towards the commercial downtown to the north. The iconic Elisabeth Walton Potter summed up the site best noting "the rational, terraced scheme was enhanced by park-like landscaping which provided an effective foil for buildings of reinforced concrete."2

There are common design elements found in all of the buildings and structures that create a sense of design unity throughout the Salem Civic Center Historic District and speaks to the monumental nature of the Brutalist style. In 1982, the Salem Civic Center received a Merit Award from the Oregon Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects. In the announcement the Chapter wrote, "The extensive repetition of architectural elements provides continuity."3 All buildings were historically square or rectangular, and this shape is carried over into the decorative features of the Mirror Pond (Images 8-10).

Each building from the period of significance has a flat roof with a wide, concrete panel parapet and features vertical concrete columns that create numerous bays. There are narrow, horizontal lines in the concrete that run around the buildings, especially along the parapets. Concrete is the primary building material around the complex, including at the Plaza Fountain, walkway railings, open space on the City Hall Parking Garage, and elements of the Mirror Pond. The poured in place concrete buildings are striated, and the ties were intentionally unfilled to avoid the appearance of patching.4

While the main building materials are concrete and glass, there is some horizontal wood paneling found in City Hall, mainly in the Courtyard. Together these common elements take seven individual resources and create one civic space for one city moving towards one future.

Character-defining features of the site include the overall layout with sweeping staircases, ramps, and sidewalks that provide continuous access from one city service to the next. Notably, the design of the Salem Civic Center took into consideration accessibility, especially for Salemites requiring mobility assistance.5

The overall landscaping scheme conveys the open and welcoming intent of the Salem Civic Center and is character-defining. The site – including the Mirror Pond and use of Pringle Creek – was intended to offer green space (and therefore capitalize on federal funds for park space acquisition, discussed in Section 8). The Civic Center retains "refreshing space, colorful plants, and fountains for Salemites relaxation."6

It is less about what is planted in the planter boxes and more about their presence and the beautification and softness they offer to create a complex where people want to spend time.

Another character-defining feature is the orientation of the buildings to each other. The Central Fire Station #1 is strategically located away from city services and near main transportation arterials. It is also lowest in elevation. The City Hall and Public Library buildings are centered on the site with the most dominant presence and views. They were historically connected to each other in such a way that you could easily access all services from each other – leaving the historic main entrance of the Public Library, walking through the Plaza Fountain, and then entering City Hall. The spaces are sited and designed to provide functional government and easy access to services. Further, this layout and the common design elements found throughout integrate the individual public spaces (library, planning departments, fire, etc.) into one cohesive civic space.

These character-defining features are a reminder that the Salem Civic Center was and is "a project of the people."7 The Salem Civic Center dedication materials capture that the "massive, yet airy contemporary buildings [were] designed to create open space – space for the maximum use and enjoyment by the people of Salem."8 Each of the contributing resources within the district retain their connection with this guiding principle and the historic significance.

Central Fire Station #1 (1971; Contributing)

Located at the corner of the Trade and Liberty Streets is Central Fire Station #1. The two story, poured in place, striated concrete building has a flat roof and sits on a poured concrete foundation. The corners of the building feature simple, square columns that form a 90-degree angle but do not extend to the edge of the eave. There are also concrete columns on each of the elevations that form distinct bays (three bays on the north and south elevations, two bays on the east and west elevations). There are subtle but noticeable horizontal lines running across the concrete around the building, including on the columns, creating visual unity on the building and throughout the complex. The building has a concrete paneled parapet with an overhanging eave. The parapet features a distinct horizontal line between the panels and vertical divides aligned with the columns. Notably, the building has been painted since construction, the only painted, concrete resource at the Salem Civic Center.

The north elevation faces Trade Street and is divided into three bays by vertical concrete columns (Image 2). The east and central bays each have two openings for firetrucks with rolling doors (each with 28 clear openings; total of four garage door openings) on the first floor. On the second story, each bay has three, four pane, fixed aluminum windows. The west bay and central bay are divided by a more prominent and wide vertical concrete column that houses the interior stairwell. There is one window located on the second story of this stairwell column. The west bay has a concrete awning between the first and second story and no other architectural details – though there is a piece of the World Trade Center under the awning in tribute to the firefighters who lost their lives on September 11, 2001. Historically, this area provided an entrance and had full length windows and a glass door (Figure 14). The second story also had two windows.

The east elevation faces Liberty Street and has two bays divided by concrete columns (Image 3). The south bay has a large concrete tower for drying and rerolling fire house protruding from the main wall.

With the exception of two vents on the first story there are no architectural features on the north bay. There have been almost no modifications to this elevation with the exception of painting the hose tower.

The south elevation mimics the north elevation so that fire trucks can enter the building from the south and quickly exit out the north during emergencies (Image 4). The elevation is divided into three bays by vertical concrete columns. The west bay has a prominent and wide vertical concrete column, similar to the north elevation. The west bay has a concrete awning between the first and second stories and no other architectural details. The central and east bays each have two openings for firetrucks with rolling doors (each with 28 clear openings; total of four garage door openings) on the first floor. On the second story, each bay has three, four pane, fixed aluminum windows.

The west elevation, similar to east elevation, is divided by concrete columns into two bays. The north bay features two glass entry doors with a metal, flat roof entrance structure. The second story of the north bay has three, four pane, fixed aluminum windows. Centered on the south bay is two concrete columns with one, four-pane, fixed aluminum window centered on the second story between the two columns. The west elevation has been substantially altered outside of the period of significance, likely in 1992 when the interior of the building was altered and 2010 when the building received seismic upgrades (Figure 13).

The main alterations to the Central Fire Station #1 have occurred on the west elevation, as noted above. Windows have also been replaced on the north and south elevations. Historically all windows on the second story were one light with no panes (Figure 14). The main entrance has also been relocated from the north elevation to the west elevation. The building underwent modifications in 1992 (mainly to the interior) and 2010 when seismic upgrades were completed (metal anchors were added in the parapet though they are barely visible). Further, the building is now painted concrete, which is unlike any of the other resources at the site. Even with these alterations, the Central Fire Station #1 retains sufficient integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association. Overall, these alterations are compatible with the original design of the Central Fire Station #1 and do not detract from the historic integrity of the building or the Salem Civic Center. The primary materials – concrete and glass – and location and siting of the building– an anchor of the complex with quick access in and out of the district – are all retained.

Character-defining features of the Central Fire Station #1 include the overall design (flat roof, concrete columns that create bays, concrete parapet, horizontal lines) and materials (striated, formed concrete).

Another character-defining feature of the Central Fire Station #1 is the location and layout on the site to provide access from both Trade and Liberty Streets and the garage doors on both the north and south elevations. This allows fire trucks to enter through one door and quickly exit out another without having to back it up. The building maintains sufficient character-defining features a strong association with the overall goals of the Salem Civic Center and the siting of city services in one location for a more efficient and modern government.

Mirror Pond and Pringle Creek (1972; Contributing)

Located south of the Central Fire Station #1 and north of the City Hall Parking Garage is open space that utilizes two water features for maximum beautification – Pringle Creek and Mirror Pond. Pringle Creek runs east-west under bridges on both Commercial and Liberty Streets and between the Mirror Pond and Central Fire Station #1.9 Pringle Creek was existing on the site when the location was being considered and utilizing the water feature was an early part of the design and a selling point when trying to get the 1968 bond passed.10 Pringle Creek was minimally altered or not realigned during construction.

During the Salem Civic Center dedication, the Mirror Pond was described as being a "no-cost gravity flow water system [that] will keep the pond fresh at all times... for public enjoyment."11 The Mirror Pond is concrete lined and ranges in depth from 30" to 4' (Images 7-10). It retains a series of square, concrete slabs that contrast with the more circular, organic shape of the pond and walkways while connecting the resource to the square buildings. At the north end of the Mirror Pond are a series of concrete steps that connect it to Pringle Creek and allow water to flow down (Image 8). A sidewalk circles the entire pond and there are some wood and concrete benches scattered around the site close to the shore.

While the Mirror Pond was not meant for swimming (even though the Salem Civic Center dedication book included photos of kids splashing in the water) it provides an aesthetically pleasing landscape feature.12

Both Mirror Pond and Pringle Creek maintain a high amount of historic integrity and with the exception of some benches being removed, there have been no documented alterations to the design. With the exception of removing some benches and new plantings, there have been relatively few modifications to either Mirror Pond or Pringle Creek and the integrity is highly intact.

Character-defining features include the location, design, and materials. The square, concrete elements around the pond and leading to Pringle Creek are essential for connecting Mirror Pond with the other buildings at the Civic Center, reminding the community that it is nature with purpose (Images 8 and 10).

The sidewalks around the area also connect the district. You can easily access all of the buildings without having to cut across the grass. The Mirror Pond and Pringle Creek continue to provide enjoyment for Salemites, beautification, and connectivity for the Civic Center.

City Hall Parking Garage (1972; Contributing)

While partially connected to the City Hall building with surface level walkways and a semi-underground entrance, the City Hall Parking Garage is considered a standalone building. The poured in place, concrete building features two levels of parking. One level is entirely underground while the top level is half covered by a concrete open park space and concrete planters and the other half is open (Images 11-13). Vehicular access to the City Hall Parking Garage is from the south and beneath the City Council Chambers, which sits over the road that provides access between Commercial and Liberty Streets (Image 14). North of the City Hall Parking Garage is the Mirror Pond. There is a set of stairs on the north elevation that provide access to all parking levels and the open space on the roof. The City Hall Parking Garage was sited intentionally to allow for the minimum amount of excavation, which afforded the City some cost savings in a ballooning project. The City Hall Parking Garage retains a high degree of historic integrity and has had relatively few modifications made since construction in 1972. As the City Hall Parking Garage used to house the Salem Police Department fleet until 2020, there have been some gates, lighting, and security added. However, none of the alterations have impacted the integrity of design, materials, or workmanship.

Character-defining features include the concrete materials, design, and location. Not only does the location of the building provide easy access to City Hall but the siting allowed for cost savings on excavation during construction. The flat roof and landscaping elements are also an important trait as it provides cars protection from the elements, a community space to gather, and something more than a paved parking lot. Like all other buildings on the site, the materials are formed concrete and there are horizontal lines. The sweeping staircase on the north elevation provides continuity and access around the site that is essential for the unity of the district.

City Hall (1972; Contributing)

City Hall is located at the center of the Salem Civic Center site. It can be accessed from the north elevation from the City Hall Parking Garage or from the Public Library and Plaza Fountain on the south elevation. It is a poured in place, striated, concrete, three-story, U-shaped building with waffle slab construction. The building has a flat roof with some mechanical equipment on the roof and a concrete panel parapet with a horizontal line running around the entire building. The corners of the building feature simple columns that form a 90-degree angle but do not extend to the edge of the eave. The building relies heavily on open circulation (see Courtyard description below). City Hall houses the majority of city services including the Mayor's Office, Public Works Department, Community Development Department, and other essential services. From 1972 until 2020, City Hall was also home to the Salem Police Department.

The south elevation of the building faces the Public Library and Plaza Fountain and was the intended main entrance of the building (Images 17 and 18). It can be accessed by concrete stairs or ramps. From this perspective, the building appears to be two-stories. The south elevation has nine bays demarcated by concrete columns that run from the ground to the parapet. For this description they are numbered from one to nine from west to east. Bay one features six, single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the first story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom.

The second story features six single light, fixed, aluminum windows. Bay two is similar though there are only four windows on the first story and a portion of the bay is open to the entry plaza. Bays three to seven open on the first floor to a covered, entry plaza. The second story has a total of 24 single light, fixed, aluminum windows. Bays eight and nine have concrete panels on the first story and a total of 12 single light, fixed, aluminum windows. The ceiling in the covered entry space shows off the waffle slab construction methods (Image 20).

The west elevation faces Commercial Street and appears to be two-stories from this perspective (Image 17). It is divided into six identical bays each with six single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the first story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom.

On the second story, each bay has six single light, fixed, aluminum windows. The north two bays have an exposed bottom floor with single light, fixed, aluminum windows. There are no entrances or other architectural features on this elevation.

The north elevation is three stories and is split by the Courtyard and City Council Chambers to create the building's U-shape (Images 15, 16, and 19). The west half of the north elevation features a staircase on the east and then an open-air hallway that provides access to city services and a view of the Mirror Pond and downtown Salem.

The two bays west of the hallway each have (from ground level up) four single light, fixed, aluminum windows on the ground story; four single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the second story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom; and four single light, fixed, aluminum windows on the top story.

The east half of the north elevation also has an open-air hallway that provides access to city services. The eastern most bay has (from ground level up) a concrete panel, wood door, and two windows with a horizontal wood band on the first story; six single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the second story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom; and six, single light, fixed, aluminum windows on the top story.

The west bay has (from ground level up) four windows with a horizontal wood band on the first story; four single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the second story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom; and four single light, fixed, aluminum windows on the top story.

The east elevation has four bays, each distinguished by concrete columns that run from the ground to the parapet and is three-stories (Image 19). The ground level features access doors and a number of meters and other utilities. On the second story, the south bay is enclosed with concrete panels, but each of the other three bays has six single light, fixed, aluminum windows inset on the second story with a decorative metal panel above and an outward sloping concrete feature on the bottom. Each bay of the third story has six single light, fixed, aluminum windows.

City Hall has been subject to relatively few exterior modifications since 1972 construction. There are likely some changes to the ground story of the east elevation for new utilities, but the rest of the building remains highly intact based on historic photographs and a review of building permits (Figures 7 and 12).

One modification is that some city services have been relocated outside of City Hall. In 2020, the Salem Police moved to a new station north of downtown, and the other city agencies (e.g., Urban Renewal) are also located offsite. However, the majority of city services are still located in this building and overall it retains its association with providing easy access to government in one space. The building retains an incredibly high degree of historic integrity, especially with regard to materials and design, which are related to many of the character-defining features.

Character-defining features of the City Hall exterior include the concrete columns that create distinct bays, the fenestration pattern and details (e.g., outward sloping concrete below the windows), the visible elements of waffle slab construction in the ceiling, the plexiglass roof over the courtyard space, striated concrete, and the U-shape. Tie holes in the concrete piers (Image 22) were intentionally left open to avoid a "patched" appearance.13 At the time of construction, the plexiglass skylight over the Courtyard was the largest on the west coast and the Fire Marshal had to grant special permission and extra review to ensure it met code and would not pose a safety risk. Glass doors on the south elevation were not intended to be a barrier but were instead designed to prevent winter weather from entering the building.

Another character-defining feature is the open access to and viewing of all city services. Floor to ceiling windows allow citizens to see their government in action and more actively participate (Image 22).

Another character-defining feature of City Hall is the location with a prominent view overlooking the commercial downtown.

City Council Chambers

The City Council Chambers are included within the resource count for City Hall but are worthy of a separate description. The Chambers sits on concrete columns and spans the access road that connects Commercial and Liberty Streets and offers vehicular access to the City Hall Parking Garage (Image 14).

There are recessed lights on the underside of the building. There are two double-door entrances on the south elevation of the concrete building, each accessed by pedestrian walkways that connect the Chambers to the second story of the City Hall (Image 21). Historically, the Council Chambers entrance features large, wood doors with bronze carvings (Figure 22). These doors were replaced c.2021 with lighter, more secure, weather resistant metal doors (Image 37).14 The building has a flat roof and concrete panel parapet with overhanging eaves. Notably the parapet does not feature any horizontal lines that are found on other buildings, including City Hall and Central Fire Station #1.

The south elevation of the City Council Chambers has three bays (Image 21). The east and west bays are inset and feature the two sets of double-doors and walkways noted above. The central bay has concrete panels, wood vents, and a window. The west elevation has large glass windows on the corners and five concrete panels in the center (Image 16). The north elevation has six, large glass windows that offer a commanding view of the downtown (Image 16). The east elevation mimics the west elevation in that it has large glass windows in the corners and four concrete panels in the center (Image 13).

The interior walls have horizontal Red Oak wood siding (which was actually a flooring material) and there are four striated concrete columns in the Chamber, covered in pictures of former mayors (Image 39). The ceiling is tiled and the center, inset lighting feature is a series of wood squares, similar to the design of the waffle slab ceiling found throughout City Hall (Figure 23). The Mayor sits with their back facing the south elevation and flanked by the City Manager and City Attorney. City Council member desks run perpendicular to the Mayor, with four Council Members on each side. There are two podiums for the public to offer testimony, both facing the Mayor and Council. There is tiered public seating surrounding the Council on the east, west, and north. There are many sculptures and pieces of donated artwork located throughout the Chambers.

Character-defining features of the City Council Chambers are the materials (concrete exterior with wood and concrete on the interior) and the separation from the rest of City Hall. The interior layout is also important as it allows for the public to be able to look down upon its elected representatives. While seating and desks have been replaced (Figures 15 and 23), this overall spatial organization remains, and the integrity of the City Council Chambers is highly intact.

Courtyard

Another portion of the City Hall Building that deserves a standalone description is the Courtyard. This best speaks to the open nature of the City Hall and the goal that city services be open and accessible.

While most of the site has a combination of stairs and ramps for greater accessibility, the courtyard has a series of staircases and elevators. There is one sweeping, center staircase and then multiple staircases on the east and west wings of the building (Image 23). The elevator is easily accessed from the main entrance on the south elevation. The center plaza is open and covered with an accordion, plexiglass ceiling so employees and Salemites can use the space year-round (Images 24 and 25). The ground floor of the courtyard has a series of planters with ponds and naturalistic plantings (Images 21 and 23). City services enclose the courtyard and can be accessed by concrete walkways with simple railings. The walls are a combination of horizontal wood paneling and glass (Image 22). This allows Salemites to watch their government working for them.

The courtyard is one of the most character-defining spaces of the Salem Civic Center. The combination of materials and the overall design speak to the goal of the Civic Center – public accessibility to Salem's efficient and modern government. The space is open, and access is provided from multiple directions and methods. It is covered to keep out the rain, but the plexiglass ceiling allows for the sun to shine through.

The concrete planters and benches allow for people to sit and enjoy the space. Included in the character-defining features of the courtyard are those structural items that were gifted to the city by Salemites. This primarily includes decorative doors located within office spaces and artwork (Images 38 and 40). It is important to note that Salem has a robust and active Arts Commission. While donated art pieces from the period of significance – like "Untitled" by Wiltzin B. Blix (Image 40) – are important to retain, it is more about using art in the space to create community that should be considered character-defining.15

Plaza Fountain (1972; Contributing)

Located between the Public Library and City Hall buildings, Plaza Fountain was completed in 1972 and was the location of many Civic Center dedication activities (Figure 11). The entire Plaza is concrete and features 33 concrete triangles of varying sizes arranged in a circle. Some of the triangles are used to support wood benches. Located in the middle of this feature was a water fountain that now displays a statue. It was decommissioned in c. 2002.

In 1987, Plaza Fountain was renamed and dedicated "Peace Plaza" to represent "tangible expressions of community concern about world peace and even better neighbor-to-neighbor relations in Salem."16 With this new name and more guided purpose, the Plaza underwent a series of modifications. The Peace Wall located east of the center of the plaza was built in 1988 and is not character-defining to the Plaza, though it also does not detract and nor diminish integrity considering the materials used and location (Image 35).17 A number of flag poles were also installed to display flags from Salem's Sister Cities. Even with a new name, purpose, and modified infrastructure, the Plaza Fountain retains sufficient integrity from the period of significance with regard to design, materials, and association to be a contributing resource.

Character-defining features of the Plaza Fountain are the location (connecting the Public Library to City Hall) and also the concrete materials, which connects the object to the other buildings. The open-nature and focal point (fountain/statue and concrete triangles) are also an essential element of the resource.

Salem Public Library (1972, 1991, 2021; Non-Contributing)

The Public Library was constructed in 1972 as one of the key components of the Salem Civic Center. It is located south of City Hall and the Plaza Fountain. The concrete building is three-stories and the primary entrance is on the south elevation facing the Library Parking Garage (Image 31). There is also an entrance on the north elevation from City Hall and the Fountain Plaza, which was the main entrance until renovations were completed in 1991 (Image 29). The building is surrounded by concrete surfaces with ramps and staircases. The Public Library was intentionally constructed as one of the primary features of the site and is partially built into the hillside. However, major renovations to the building in 1991 and seismic upgrades in 2021 have substantially diminished the historic integrity of design, materials, workmanship, and feeling. Therefore, the Public Library building is non-contributing to the Salem Civic Center complex.

In 1991, the building received an addition on the south elevation and the primary entrance was relocated from the north (towards Fountain Plaza and City Hall) to the south (facing the new Parking Garage). This addition, which is partially circular in nature, included a new auditorium space and children's area. It was also during the 1991 renovations the mezzanine and breezeway on the north elevation was enclosed and windows were added (Figures 11 and 16). Overall these renovations added 25,000 square feet to the building and diminished the connection of the building to City Hall and the overall space (specifically sidewalks around the site connected to the second-floor breezeway on the north elevation).

In 2020-21, the Public Library received seismic upgrades, including adding shear walls on all four sides of the building that stretch from the ground to the concrete parapet. These shear walls are continuous and do not feature the bold horizontal elements found on the historic Public Library. The three concrete bays on the west elevation were also removed and replaced with glass windows to allow for more natural light in the building (Image 30). An external concrete staircase that once connected to the breezeway was removed from the west elevation.

While these renovations have created a Public Library that safely meets the needs of the community, collectively they have yielded the building non-contributing as it is no longer reflective of the period of significance and context. The south elevation addition, shear walls, opening of the west elevation bays, and the substantial changes to the north elevation – relocating the entrance, enclosing the breezeway –

have substantially and irreversibly altered the historic design. While the building is still concrete, glass is now an overpowering material of the Public Library, especially on the north and west elevations. The south elevation does not retain any elements from the period of significance. Given the overall loss of both design and materials, the integrity of workmanship as reflective of the 1970s craft is also diminished.

Many of the concrete finishes have been replaced with glass and the shear walls break up the once unified look of the building. The building conveys a much more modern feeling and character.

Considering these substantial renovations, the Public Library is non-contributing.

Library Parking Garage (1991; Non-Contributing)

Built in 1991, the two-story, concrete Library Parking Garage is located on Leslie Street between Commercial and Liberty Streets with entrances on the north and south elevations. There is both below ground and roof top parking.

Historically, the location of the Library Parking Garage had surface parking, a Children's Play Area, and green space with landscaping and sidewalks (Figure 17). The only element that remains is a stepped concrete and brick structure between the south elevation of the Public Library and north elevation Library Parking Garage entrance (Image 34).

Due to parking limitations and expanding library needs, the building was constructed in 1991. It is architecturally compatible with the overall Salem Civic Center with regard to style, scale, and materials, and does not detract from the setting, design, association, and feeling of the district. However, as it was built outside the period of significance, the Library Parking Garage is non-contributing.

Integrity

Even with modifications to the Public Library building and the addition of the Library Parking Garage, the Salem Civic Center retains sufficient integrity to convey significance under Criteria A and C in the area of Community Planning and Development. The location remains the same as constructed in 1972. When Salemites were asked to pass the 1968 bond measure and fund construction (discussed below), they were also asked to select the location from two options. They overwhelmingly elected to construct at the present location which in part speaks to the desire to have city services overlooking downtown. 18 With the exception of the Library Parking Garage, all of the buildings and landscaping features remain in the same locations as originally constructed. The design of the Salem Civic Center also remains relatively intact.

Even though some contributing buildings have undergone slight changes, like the Central Fire Station #1, contributing resources each individually retain their overall design with regard to form, style, and plan.

The City and architects made very deliberate choices. The organization of the buildings, specifically the City Hall and Public Library sitting centered on the site and at the highest elevation, and their surroundings are still intact. The stairs, sidewalks, and ramps connect the space and create an accessible Civic Center complex. As the design of the complex is highly intact the historic function and significance is strongly conveyed through the property.

The overall design of the property – including the planter boxes, greenery, water features – led John Terry, news editor of The Capital Journal**, to conclude that the "overall design of the place lends itself to all sorts of activity ungovernmental [sic], and, when the grass and trees gain some maturity, the complex should prove one of the best places in town to go to simply goof off."18 This is strongly retained, though probably more frowned upon.

While there has been development and new construction adjacent to the Salem Civic Center, the setting remains highly intact and the character of the complex from the period of significance is still conveyed.

The property is still sited between two major north-south streets and south of the commercial downtown.

Natural topography and green space are retained. Further, as noted above for design, the sidewalks, stairs, and ramps are in their historic locations. All of these elements together allow the property to serve Salemites and provide accessible government services.

The exterior material integrity of the Salem Civic Center is highly intact for most of the contributing buildings. The Central Fire Station #1 has been subject to seismic upgrades and window replacements, but these new introductions do not detract. The City Hall Parking Garage and City Hall building have had almost no exterior modifications. Further, Mirror Pond, Pringle Creek, and Plaza Fountain have had almost no exterior materials modifications. The workmanship of the Salem Civic Center is also highly intact and retains the finishes and aesthetics of the Brutalist style that was common for this type of public building during the period of significance.

As a property that reflected what the City of Salem wanted to become, the integrity of feeling and association are essential for the property to continue to convey significance. The Brutalist style harkens back to period of significance and is reflective of the ideals of Salem at the time. The district is still strongly associated with the popular style from a time period when there was an increasing notion that government should include robust civic engagement and be more accessibly. The historic aesthetic and character is strongly intact. The Salem Civic Center was designed to guide Salem into the future and was a bold statement on the landscape that Salemites valued efficient government and wanted city services in modern buildings that were for their enjoyment and benefit. The link between the district, the architectural style, and the development of Salem is still conveyed to those in the community. Therefore, the Salem Civic Center continues to be directly related to this feeling and association.

-

City of Salem Dedication Committee, Civic Center '72: Our Pride and Heritage (Salem, OR, 1972). ↩

-

Elisabeth Potter Walton to Linda Norris, January 23, 2019, one file with the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office. ↩

-

From the Salem Civic Center File, on file with the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office. ↩

-

The poured concrete for the buildings was formed using Weyerhaeuser wood siding materials that were discontinued right as the project was coming to a close. The City had to search warehouses across the country to find enough to complete the project, and appropriately bragged that it could never be duplicated (Civic Center Fact Sheet, August 1972, Civic Center Files, City of Salem). ↩

-

In 1970, Joseph Fitzpatrick, who was the Salem Civic Center Project Manager, wrote a memo stating "there is wheel chair access throughout the entire project from Trade Street to Leslie Street whereby a wheel chair person can go from any point in the area to any other point without going up one step or without getting out of the wheel chair." This extended to also making sure that restrooms offered accessible stalls and proper wayfinding graphics (J.F. Fitzpatrick to B.T. Van Wormer, December 7, 1970, Civic Center Files, City of Salem). Advocacy for disability rights increased in the 1960s and early 1970s and the Salem Civic Center incorporating accessibility shows an awareness of these changes and a desire to create an inclusive government, at least for the time. ↩

-

City of Salem Dedication Committee, 14. It is worth noting that the fountain in the Plaza Fountain has been decommissioned. However, there are still other water features around the space and integrity has not been diminished. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The Commercial and Liberty Street bridges are located outside of the Salem Civic Center historic property boundary and are not included in this nomination. They pre-date the period of significance and are not associated with the areas of significance. There were no notable upgrades to the bridges during construction of the Civic Center. ↩

-

Pringle Creek had been modified by Boise Cascade, who had a large facility west of the Salem Civic Center. Based on a review of historic aerials, the location of Pringle Creek was not modified during construction. ↩

-

City of Salem Dedication Committee, 14. ↩

-

"Mirror Pond Not Designed For Swimming," The Statesman Journal, July 23, 1972. At one point it was used by the Santiam Flycasters Club to practice fly fishing casting ("Fish ‘shut out' flycasters club at city hall pond," The Statesman Journal, July 15, 1977). ↩

-

"Civic Center Fact Sheet," August 1972, Civic Center Files, City of Salem. ↩

-

The original carved wood doors were retained and will be displayed at City Hall. At the time of writing this nomination, the Salem Arts Commission is still determining an appropriate location. ↩

-

One of the major components of the Salem Civic Center dedication was the "Mayor's Invitational Art Show" which included 37 pieces either purchased or gifted for the Civic Center specifically. ↩

-

Mark Hatfield, "Our work must continue," The Statesman Journal, April 15, 1987. ↩

-

"Civic Center Plaza Shows Commitment," The Statesman Journal, July 6, 1988. ↩

-

John Terry, "Civic Center a great place to goof around," The Capital Journal, August 19, 1972. ↩

Statement of Significance

Text courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, a program of the National Parks Service. Minor transcription errors or changes in formatting may have occurred; please see the Nomination Form PDF for official text. Some information may have become outdated since the property was nominated for the Register.

Summary Paragraph

The Salem Civic Center Historic District, entirely completed in 1972, is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places at the local level under Criterion A as the district represents the ideals of Salem's community planning and development in the late 1960s/early 1970s.1 The property is also eligible for listing under Criterion C as an important local example of the Brutalist civic campus. The period of significance is 1971 to 1972, which spans the dates of completion and dedication. The property has five contributing resources –Central Fire Station #1, Mirror Pond and Pringle Creek, City Hall Parking Garage, City Hall (including City Council Chambers), and Plaza Fountain – and two non-contributing resources – Public Library and Library Parking Garage. Following World War II, Salem was rapidly growing, and the 1897 City Hall Building was no longer sufficient to house city services and meet the evolving needs of Salem government and increased expectations of civic engagement and participation in decision making. For over two decades, the community completed multiple studies to determine the best approach for a new civic center, and Salemites ultimately showed their strong support for the construction of a new complex that would unite all city services while also providing accessible public spaces. The Salem Civic Center was considered modern, functional, accessible, and for everyone's enjoyment and use. The Salem Civic Center Historic District is the best local representation from the period of significance of what Salemites wanted in their government and community, and how they wanted it to look, as they ventured into the future as a "safer, healthier, and more livable... modern urban community."2

Narrative Statement of Significance

Brutalism

Deriving its name from the French phrase for "raw or unfinished concrete" – béton brut – Brutalist architecture is loved by some and hated by many.3 The iconic Le Corbusier is credited with the first Brutalist building (Unite d'Habitation, Marseille, France, 1947-1952) which placed emphasis on the structure instead of decoration, to "build transparently, cleanly, and truthfully."4 In 1957, Alison and Peter Smithson published a short but powerful essay on Brutalism, the movement and style they were in large part responsible for defining and creating.5 In this often-cited piece they argue that past objectives for change can be "become useless... so new objectives are established."6 Brutalism considers the "problem of human associations and the relationship that building and community has to them."26 The Smithson's argue that Brutalism, as a new architectural style, is a response to society. If one is to sit and be critical about the use of raw concrete or the blocky shape of the building, then the intention of Brutalism is lost. For "its essence is ethical" not merely a style or aesthetic.7

The Smithson's expanded their notion of Brutalism to go beyond individual buildings, placing an emphasis on "town building" and planning. Peter Smithson described this as "the way the buildings themselves fit together and interact with each other which creates the actual places in which you move, and have a feeling of identity or lack of identity."8 To design and construct in Brutalism was to accept "what is going on" and reject "chi-chi," which is when one "cannot be bothered to think out what the situation is, and how to work it out properly, and drops back into a formula of doing it which is a sort of lie."9 The Smithson's also placed an emphasis on "urban re-identification" and architecture trying to provide a "feeling that you are somebody living somewhere."10 This was carried out by categorizing spaces for different functions and land-uses. While this concept was not necessarily innovative or revolutionary, they carried it out by focusing on "connectedness." Peter Smithson said "we regard ourselves as functional, and therefore there is not only space in the town, but that space must signify what is going on, its function, and one of the things that we have to face in the twentieth century is that the space in towns has to indicate that it is a net of communication... there is more feeling of connectedness rather than the feeling of being in villages which is self-contained."11 This was reflected in their designs by incorporating different sized buildings with different functions into a cluster that would be "comprehensible to its inhabitants."12

Brutalism also focused on raw, "real" materials – "wood, and concrete, glass, and steel, all the materials which you can really get hold of" – instead of the materials of the 1940s, which Alison Smithson described as "some sort of processed material such as Kraft Cheese."13 Brutalist materials were "bold and confrontational... heavy, rugged forms forged of inexpensive industrial materials that disguised nothing at all."14 But even though the name is derived from a material, Brutalism cannot be defined only by the materials, and instead should be grounded in "honesty: an uncompromising desire to tell it like it is, architecturally speaking."15 Even the father of [New] Brutalism, Peter Smithson, admitted "I am obsessionally [sic] against the brick... [but] if common sense tells you that you have to got to make some poetic thing with brick, you make it with brick."16

Brutalism, with its "heavy, monumental, stark concrete forms and raw surfaces," was – as Ada Louise Huxtable put it – a "passing style."17 While the first Brutalist building was built in the last 1940s, the style fell rapidly out of popularity by the mid-1970s. Concrete was becoming more expensive and critics became more outspoken against the "experimental forms...[and their disconnect] from the historical symbolism of architectural form."18

However, this time period aligns with the same era America was seeing rapid construction of publicly funded infrastructure, especially public housing units and civic spaces. As such, there are swaths of many urban areas that feature Brutalist structures and designs. The popularity of the style also aligns with a time when civic spaces, especially city halls, were being built with new ideals and goals surrounding public engagement in government decisions.19

Civic Spaces in the Late 1960s and Early 1970s

Civic spaces and city hall buildings offer a space for a citizen's to "participate directly in making public policy."20 The "human conceived, designed, and constructed" nature of these spaces is evidence of the "political meaning" and purpose of the time period.21 The "social meaning" of architecture says something about "those who inspired, built, arranged, and use it... nonverbal commentary about people, politics, culture, and civilization."22

Cultural shifts regarding public participation in government in the 1960s and 1970s are evidenced in the architecture and design of civic spaces from this era. Federal funding to carry out the goals of the Great Society and fight the War on Poverty helped city governments physically grow at the same time "a new ethos of citizen participation in government emerged, stressing citizen boards, the prompt consideration of taxpayer complaints, minority employment in the bureaucracy, and an active citizen voice at public hearings and in city-council meetings."23 Federal laws from the time, specifically the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, required programs be carried out with "maximum feasible participation" from local communities.24

It was also during this era that cities were building more "comprehensive civic centers" that included multiple public buildings with landscaping features (plaza, park, etc.) to create unity. This time period likewise saw the separation of city council chambers from larger city hall buildings. This disconnected the City Council from the day-to-day functions of government and created a sense of importance. Yet, the separation also managed to increase access and public accountability as sweeping staircases were replaced with ground level buildings accessed by ramps.25 The grand, elite notion of government was physically taken down a notch. City, county, and state governments in the 1960s and 1970s relied heavily on the notion of community participation in policy development, and the architectural style adopted – often Brutalism – helped to accomplish this.

The Brutalist style lent itself well to public spaces and civic centers because of the process behind it – "starting with a conclusion and then working back towards a beginning."26 The essence of the building – or what architect Louis Kahn called the "form" – should be at the center and then the "design" can create unique circumstances.27 At their core, city halls contemporary to the Salem Civic Center were "designed for public access to civil servants and services."28 There was an expectation that city hall provide a space where the public can interact with democracy and be heard. Outdoor plaza spaces that connect "into the building through ramps and steps that [imply] accessible officials" are a key feature of Brutalist civic spaces, including the Salem Civic Center.29 Further, the concrete materials "suggested a fortified barricade and the weight of authority."30 Public spaces "become significant symbols that remind everyone whose attention they command that they share a common heritage and a common future..."31 This is the essential form of a civic space and city hall, and from there individual architects added individual design elements for the site and the community.

Buried in rolls and rolls of microfilm about the construction of the Salem Civic Center is a two-page flyer for a new city hall in Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky. Designed by noted architect Edward Stone and finished in 1965, Paducah's City Hall is not really Brutalist and is only one building on one city block, though it does have a large interior plaza and took twelve years to get approved by local voters, which is very similar to Salem's Civic Center.32 However, the most striking similarity and why this building was likely brought to the attention of Salem's City Manager and Civic Center Project Manager is that it was described over and over as "inviting."

During the building dedication, William S. Foster, editor of American City Magazine, described the new city hall as "beautiful, delicately design, and inviting."33 Foster went on to say that old city hall buildings were "temple like... with long flights of steps which demean people and separate them from their government."34 In a shift away from earlier eras when government was elitist and participation was minimal, the architecture and planning behind civic centers and city halls of the late 1960s and early 1970s, was about connecting people with government. The City of Salem, though not without struggle, would adopt these Brutalist design elements and community planning ideals for their new Civic Center.

Salem, Oregon

Note: Given the number of National Register of Historic Places listed properties, including historic districts, in Salem, Marion County, the following historic context on Salem has been kept relatively brief and focused to best illustrate the areas and period of significance.

The City of Salem is located in the traditional homelands of the Santiam band of the Kalapuya. Salem's commercial downtown – located immediately north of the Salem Civic Center – was known as Chimikiti. Often written as Chemeketa today, this translates to "gathering place."35 Historic documentation and the archaeological record indicate that the current location of Salem was a winter village for the Santiam bands since time immemorial.56 The location of the Salem Civic Center Historic District was largely Oregon Oak prairie with intermittent springs.

The non-Native history of Salem does not extend nearly as far back as Tribal use of the region, and instead begins in the 1830s when a group of Methodist missionaries led by Jason Lee settled ten miles north of present-day Salem. In July 1840, Lee and his missionaries started the construction of a lumber and flour mill at High Street and Mill Creek near present-day downtown Salem.36 This location was selected as Mill Creek offered more ideal water flows for power generation than the Willamette River. Lee's mill dissolved in 1844, and Salem was surveyed in 1846.

Salem was designated the Marion County seat in 1849 and that same year the first post office opened.37 In 1851, Salem was named the capital for the Oregon Territory after the original territorial government had convened in Oregon City in 1849. Oregon received statehood on February 14, 1859 and while it has seen multiple capitol buildings, Salem has been the capital city since. 38

With the discovery of gold in California and southern Oregon in the 1850s, Salem become more prosperous and well established with hotels, newspapers, and stage lines in the downtown. Growth continued during the 1870s and 1880s evidenced by a bustling commercial downtown built of brick instead of wood. In the early 1900s, transportation infrastructure continued to grow in Salem, with a robust streetcar system, paved roads, and the first automobiles. The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Willamette River also helped to sustain local businesses.39

Population growth in Salem took a dip during the Great Depression, but the Works Progress Administration completed a number of public infrastructure projects in the city, including highway underpasses and new buildings around the Capitol Mall, including the State of Oregon Library building and landscaping. This work also included construction of a new capitol building in 1938 as the prior one burned in 1935. In 1940, Salem celebrated the centennial of Jason Lee constructing his mill and the population was just under 31,000.

Following World War II, during which the city saw relatively few new infrastructure projects, the city began to geographically expand with post-war housing subdivisions around the city. By 1950 the city had approximately 43,000 residents and the focus of infrastructure was shifting towards the automobile with the construction of downtown parking garages and wider bridges spanning the Willamette River (e.g., the Marion Street Bridge, 1952). Salem also made additional improvements including an upgraded water supply system in 1952, demolishing and rebuilding public school buildings, and welcoming new businesses to the downtown. In 1952, the 1873 Marion County Courthouse was demolished for the construction of a more modern building. Twenty years later, Salem's City Hall would see a similar fate. Salem's population continued to boom into the 1960s.

Interstate 5 between Portland and Eugene was completed and development near this corridor increased, pushing Salem to the east. In 1961, the Salem Urban Renewal Agency was formed and with it came great changes to the community – both beautification efforts and the demolition of historic resources.40 It was also during the 1960s, after years of trying, that Salem's government was finally ready to physically move out of the past and into a new complex that would serve Salem for the future.41

Salem's City Government

Today, Salem has a population of over 175,000 and the largest employers in the city are primarily public entities – state government, Salem-Keizer School District, and Marion County.42 While Salem's history, development, and growth has always been aided by county and state government being located within the city, Salem's own city government developed somewhat later and was not established until February 18, 1857 when, in the council room at the Marion County Courthouse, Wiley Kenyon was declared the first mayor and four aldermen were selected. Their first order of business was to establish a committee to "draft rules for the government of the common council."43 Streets and sidewalks were the next thing the council tackled, though efforts to prohibit gaming and stop swine from running freely came shortly after. In 1865, the City Council appropriated funds to purchase land for the fire department and in 1866 four special policemen were hired to address a "crime wave of sorts." In 1870, the City Council was meeting in the Patton Building (on State Street between Commercial and Liberty Streets, demolished in 1965) and it would not be until 1893 that the city would pursue funding for the construction of a dedicated city hall with space for the fire and police departments.

Located at the corner of High and Chemeketa Streets, designed by Walter D. Pugh, and built by Southwick and Hutchins, Salem's first city hall cost $80,000 and was 20,000 square feet (Figure 5). While construction started in 1893, the building was not completed until 1897 due to funding struggles and disagreements over who was responsible for what (including gratings and areaway walls for the basement).44 In the 1890s, Salem had a population of around 6,000, but by 1960 the population of Salem was just shy of 50,000 – 44,000 more people in need of city services than the 1897 City Hall was designed to accommodate.

In addition to struggling with building capacity, Salem's government structure itself underwent an overhaul in the late 1940s in an effort to become more efficient. In 1939, Salem's government was called a "three-ring circus" as it had one mayor and 14 city councilmembers. Each served for no pay and was responsible for the management of city departments.45 In May 1946, Salem voters agreed to restructure city government to have one mayor, seven councilmembers, and a city manager responsible for the day-to-day operations of city departments – a councilmanager form of government.[^67] This was implemented in January 1947 and J.L. Franzen, Salem's first city manager, said that the objective of this type of government was to "work out ways to serve better [with] utmost efficiency in administration."46 However, this new type of government continued to serve in out of date and inadequate buildings.

By the 1960s, Salem city services were scattered in six different locations around the community. The City Engineer had offices in West Salem, the City Planning Director was located in the County Courthouse building, and the Parks Department was two miles south of City Hall.47 The City Hall building was also deemed too difficult to heat and cool with inadequate restrooms and limited parking.

Designed during a time of horse drawn fire engines, the building was not easily adapted to accommodate changes in fire technology, mainly automotive fire engines, and the existing space lacked appropriate living quarters for the firefighters – the area for hay storage had been converted into a kitchen. The Salem Police Department was located on the first floor of City Hall, but the conditions were dreary and basement like, making it difficult to retain officers (Figure 6).

Further, the system of transferring prisoners from the basement jail to the courtroom left much to be desired with regard to security.48

By the 1960s there were similar outdated and inadequate buildings for the Public Library. In 1904, the Salem's Woman's Club hosted a "book social" and received fifty donated books, with more and more coming each day, and with this Salem's Public Library was born. Eventually the Salem's Woman's Club received permission from the Mayor and City Council to use "the east end of the council chambers" as a makeshift library. 49 Local carpenters volunteered to build shelves and the Club continued constant fundraising efforts, with little financial support from the city.

In 1912, after the Salem's Woman's Club passed control of the library to the city, funding from Andrew Carnegie allowed for the construction of a 9,600 square foot Public Library building. But by 1968, there was no more shelf space, no off-street public parking, and no administrative spaces. It was clear that Salem's city services were designed for a Salem that no longer existed – a smaller population that relied on different transportation methods and had different needs. As Salemites planned for their future, they had to address their civic needs, and needed a physical manifestation that represented these goals and ideals.

Getting to the Salem Civic Center

The first documented calls for a dedicated Civic Center space to replace the 1897 City Hall occurred in 1947 when the Salem Chamber of Commerce published the "Long-Range Plan for Salem, Oregon, First Annual Progress Report." This report called on Salem "as the capital city, [to] lead the way in civic center development" and act quickly.50

Act quickly they did not and the initial discussion of a civic center sat idle until 1958 when the Chamber of Commerce completed a second study that looked at "future urban growth throughout the region."51 The Committee on Building Needs – a subcommittee of the overall Citizens' Conference for Governmental Cooperation – concluded that "government offices should be centralized to give the best service to the public and permit best coordination, administration, and control."52 The recommendation was specifically for Salem to plan for a "city-county annex adjacent to the Marion County Courthouse...[where] city departments could be located in close proximity to related county activities in the same building."53

At this point, both the Salem City Council and Marion County Board of Commissioners requested that James L. Payne, a local Salem architect, start to plan the specifics of this shared space. Payne submitted his final recommendations in 1963, which included a "city-county office building, library building, central fire station, and prison camp" all located near the existing County Courthouse at High and Court Streets (built in 1954 and designed by Pietro Belluschi).54 The $3.3 million bond measure that would have allowed for the construction of this shared facility was rejected by voters in May 1964.

Even after facing recent defeat, considerations about a new civic center just for Salem continued. In 1965, Mayor Willard Marshall launched a series of ten studies looking towards Salem in the year 2000. Referred to as the Community Goals Studies, topics considered ranged "from what to do about the 1893-vintage City Hall to what to do to help the elderly combat boredom."55 Salemites formed these groups and ultimately made recommendations and guidelines to the City for "genuine needs, and a long-range program" for how to accomplish this.56 The entire process took 14-months and involved over 130 community members.57 Referred to as the "Package For Progress," this ambitious plan "would see almost every city service, including parks, streets, police, fire, administration, legal, judiciary, traffic signalization and other public works, show dynamic improvements."58 However, it was ultimately up to the voters to pass the bonds needed to fund these projects, something that was often easier said than done, especially in the case of the Salem Civic Center.

The Civic Center Committee was one part of the Community Goals Studies and tackled "the immediate needs of a better governmental headquarters... to the influence on civic center planning expected from future new Willamette bridges, downtown freeways and new relationships between city and county government."59 Chaired by William L. Mainwaring, the Civic Center Committee encouraged the community to share "what they think a civic center ought to include in Salem's future."60 Early meetings of the Civic Center Committee considered multiple sites – including one north of downtown near Union Street and one extending from High Street west to the Willamette River – many of which were deemed costs prohibitive due to the required land acquisition.

Another early site was "just south of the Marion Motor Hotel," a four-block area already partially owned by the city "bounded by Leslie and Trade streets on the north and south, and by Liberty and Commercial streets on the east and west."61 This site would later be known as the Hillside Site. While slightly farther from the County Courthouse than other options, Payne believed the "site would adapt well to civic center development" and had "good possibilities."62 Certain members of the Civic Center Committee, specifically Sol Schlesinger, were concerned that voters would be unwilling to adopt a bond that could cover the cost of "extensive mall development on expensive downtown property."63 Members of the Civic Center Committee also decided they would rather see the new facility located outside of the commercial downtown core.64

As early as July 1965, the Civic Center Committee voted – seven of the eleven members in favor – to support the present-day, south Salem location citing "proximity to the downtown core, relatively low land costs, good traffic arterials adjacent and adaptability of the site to a grouping of public buildings" as key reasons.65 The City already owned the block immediately south of Trade Street. Original plans called for the city to acquire property all the way to Mission Street (which is one block south of the current Civic Center boundary).

The Community Goals Library Subcommittee voted in July 1965 that the central branch of the Public Library should be included with the civic center, as long as the civic center plans fulfilled the Committees report – which included that the building "be no less than one standard city block in size," have abundant off-street parking and would give the library building priority during construction.66 The Library Subcommittee also wanted the building to be located on top of a hill for the most prominent views and placement.

Even though early plans for the complex only called for the city hall, library, fire, and police facilities, other organizations hoped they could be included in Civic Center design. The Salem Art Association requested the Civic Center Committee include a new art museum.89 Another early topic that the Civic Center Committee faced (and a holdover from earlier conversations in 1963) was whether or not to build a "jail farm" or "prison camp" – an agricultural farm where prisoners would work, similar to those run by the State at the time.67 It was determined the City did not have prisoners serving long enough sentences to make a farm viable, and instead, a new jail would "be constructed in conjunction with a new city hall in a civic center."68

Early plans also took into consideration more than just the services that would be offered and factored in the "attractive setting" that could result from damming Shelton Ditch and creating a lake.92 In September 1965, the Civic Center Committee made their final recommendation – "locating buildings in the center, plus landscaping and parking, in four blocks extending south from downtown Trade Street – an area bounded by Trade, Commercial, Leslie, and Liberty Streets."69 The earlier two-block plan was reconsidered based on the plans for the library building, parking demands, landscaping, office space, and future growth potential. The sole dissenter to the larger plan was Sol Schlesinger, who had been a voice for fiscal conservatism from the beginning of the Civic Center Committee meetings. The two-block building would cost an estimated $4.5 million and with the $800,000 needed for additional land acquisition, the four-block Civic Center project would total $5.3 million.70

The Civic Center Committee believed they had completed sound community planning work throughout 1964 and 1965 on behalf of Salemites which demonstrated the proposed Civic Center complex would address the needs identified by the community and the City was ready to ask for funding again.

In May 1966, Salem voters were asked to fund the construction of the Civic Center Committee recommendation for the new Salem Civic Center complex. Measure 52 "would provide $4,800,000 in bonds to build not only a new city hall, but a much-needed new library and a central city fire station as well."71

Those in favor of the new Civic Center argued that the existing City Hall did not offer adequate space for city services considering the building was constructed when the population of Salem was far less (Figure 18).

Those who were opposed to Measure 52 had "concern about the lack of a final design for the building, the cost of the project, or the location."72 One Salem resident said they would be voting no given the "low sprawling design" and "wasted areas between the building and around the various building wings," instead wanting a tall, multi-story city hall.73 Another criticizer of the plan said "city fathers should come down to earth, give up the extravagance of hanging gardens and the Taj Mahal and erect a reasonably priced, adequate and beautiful city hall that can be financed and paid for."74 Other residents were unsatisfied that tentative plans for the Civic Center stating, "before I give $5.00 to a clerk I want to know what I'm getting for my money – not what it might buy."75

Ultimately, 7,715 voters were in favor while 8,653 voted no. Measure 52 failed and the new civic center remained unfunded.76 While much of the criticism about the Civic Center revolved around the design, it should be noted the City of Salem did not sponsor a contest for this design. While most Salem architects were in favor of the idea and were calling for an open competition since 1964, the City had entered into a "city-county agreement" with Payne in 1960. While some did not feel that represented a "written contract" and was for another project, Payne threatened legal action if the City opened the design up to competition or pursued another architect.77 After many opinions from the city lawyer, in late January 1966, the City Council approved a new, written contract with Payne and Settecase for the design of the Civic Center.78 Now to find the funding.

Fourth time at the polls was the charm for the Salem Civic Center project. Planning efforts for a new civic center continued even after the failed bond measure, as the condition of City Hall was not improving and the population of Salem was not shrinking. In 1968, twenty-six Salemites – representing various neighborhoods, ages, and occupations – were appointed to the Civic Building Committee, which was chaired by J. Wesley Sullivan.79 The first meeting was held in June and by late July, the Committee made two recommendations to the City Council. The first was to ask voters to pass a $6 million bond measure for the construction of the Civic Center, including the "new municipal administration building, a central public library, police and municipal court facilities, and a central fire station."80 The second issues was determining where the Civic Center should be located.

It was clear to the Committee that in order for the community to truly support the construction of the new civic center, they needed to have a direct say in the community planning decision making process and help determine the final location. Therefore, the Civic Center Building Committee asked Salem voters to select the site. The two options were the Hillside Site south of downtown (the present-day location of the Civic Center) and the Mill Creek Site north of downtown "bounded by D, Union, Winter, and High streets."81 There were concerns that the Hillside site was too close to the railroad and that the Boise Cascade papermill adjacent to the site and near the Willamette River released an unpleasant chlorine odor. However, the site would be cheaper – not only did the city already own part of the property but they would be able to utilize some federal funds given the incorporation of public parks into space – and had better parking options. There were also plans for the Hillside Site which allowed for a better understanding of costs. The Mill Creek Site was located immediately adjacent to the Capitol Mall and away from railroad tracks. However, because there were no plans available, costs and other factors, like the design, were unknown. With a new measure in front of them, many Salemites united to get out the vote for the Civic Center.